What is a "great book"? It is surely a book that stands re-reading many times, and deserves to be so read. And an educated person is one who knows the great books, and re-reads them. C.S. Lewis is quoted in Walter Hooper's Foreword to C.S. Lewis's Lost Aeneid (a wonderful new parallel text from Yale that could be used to teach Latin translation as well as introduce the Aeneid), as follows:

There is no clearer distinction between the literary and the unliterary. It is infallible. The literary man re-reads, other men simply read. A novel once read is to them like yesterday's newspaper. One may have some hopes for a man who has never read the Odyssy, or Malory, or Boswell, or Pickwick; but none (as regards literature) of the man who tells us he has read them, and thinks that settles the matter. It is as if a man said he had once washed, or once slept, or once kissed his wife, or once gone for a walk.I feel better, now, about having read The Lord of the Rings so many times. Reading great books, however (even more than one), does not suffice to make a person educated. They need to be placed in a context, they need to be loved, and they need to open the door to other interests and other

fields of knowledge. In a world where there are no longer any common binding assumptions, a world without real traditions, clinging to the great books is like clinging to pieces of wood broken off a great ship that has long since sunk. We need a ship, an adequate vision of reality, and it is the job of education to build it...

That is the kind of thinking behind the curriculum and teaching of the Thomas More College of Liberal Arts in New Hampshire, which also offers programmes in Rome and Oxford, as well as other colleges, centres for Catholic study, and study-abroad programmes - such as the following from the Center for Western Studies, which offers a gap-year on Western civilization and its religious foundations:

Cultural critics are rightly concerned that we are declining as a civilization in the West. Once Western civilization imagined and created universities, hospitals, cathedrals, great art and music, all through the thoughtful combination of Greek and Christian thought that formed the basis for Western Reason (as exemplified in the writings of Augustine and Aquinas). Today, while we may sustain the outward appearance of these institutions, our culture has lost the general Christian convictions it once held, and the result is that these institutions are becoming hollowed-out shells that resemble them on the outside but inside are increasingly confused. Universities teach there is no truth, hospitals practice abortion, great cathedrals house more tourists than worshippers, fine art has gone from public significance to private museums, and we no longer believe there is a connection between faith and reason. We are living on borrowed capital from that earlier age of faith, and many historians and cultural critics are predicting that the West as a civilization is lost. While none would want to go back to a world of plagues, feudal warfare and no plumbing (which is still the way of life in many other parts of the world), we would like to regain anything that past generations have accomplished that is truly timeless, and find ways to apply those ideas to human life in our own day.I have no first-hand experience of these gap-year programmes, but that too sounds like the right idea. And yet what do we do about other cultures, other civilizations? It's no use pretending we are not a multi-cultural society. And how do we revive faith, if that is the key to rebuilding our own civilization?

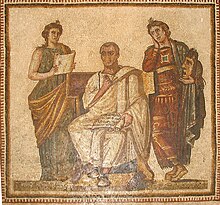

Illustration: Virgil, with Clio and Melpomene, from Wikipedia Commons.